Children’s Hospital investigators discovered two gene variants that raise the risk of the pediatric cancer neuroblastoma. The study broadened the understanding of how gene changes can make a child susceptible to this early childhood cancer and how those changes can cause a tumor to progress.

Affecting the peripheral nervous system, neuroblastoma usually appears as a solid tumor in the chest or abdomen. It accounts for 7 percent of all childhood cancers, and 10 to 15 percent of all childhood cancer deaths.

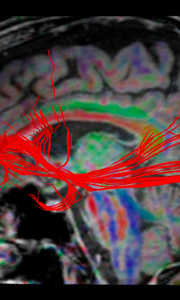

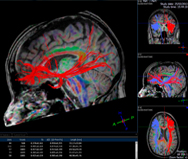

The study team performed a genome-wide association study, comparing DNA from 2,800 neuroblastoma patients with that of nearly 7,500 healthy children. They found two common gene variants associated with neuroblastoma, both in the 6q16 region of chromosome 6. One variant is within the HACE1 gene, the other in the LIN28B gene. They exert opposite effects: HACE1 functions as a tumor suppressor gene, hindering cancer, while LIN28B is an oncogene, driving cancer development.

The current study showed that low expression of HACE1 and high expression of LIN28B correlated with worse patient survival. To further investigate the gene’s role, the researchers used genetic tools to decrease LIN28B’s activity, and showed that this inhibited the growth of neuroblastoma cells in culture.

“In addition to broadening our understanding of the heritable component of neuroblastoma susceptibility, we think this research may suggest new therapies,” said first author Sharon J. Diskin, PhD.